In the previous post, we noted that Aristotle appears to have had a very different conception of myth than is common today. It is a well-attested fact of history that Aristotle learned from Plato, and the authors of Hamlet's Mill spend some time delving into Plato's texts to demonstrate that what we find there reveals the same sort of "science" disguised as myth that Aristotle understood myth to contain.

In Chapter XII of their work, Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend include a lengthy quotation from the Phaedo, focusing particularly on the description of "the earth" as seen from above, and the strange rivers which Socrates describes going around and through the earth in that dialogue. These rivers are Okeanos (Ocean), Acheron, Pyriphlegethon, Cocytus, and Styx.

In an impressive display of literary detective work, de Santillana and von Dechend reveal that the geography in the Socrates account corresponds not with earthly geography but with that of the heavens.

Socrates begins his description of "the true earth" with an analogy of the ocean, saying those who lived on the bottom of it would imagine that they inhabited the true earth, but if one could ever ascend to the surface and put his head out into the air, he would see a purer world above, not as prone to the corrosion of the sea-brine and the slime and mire of the watery world. In the same way, he says, we are living in a world less pure than the "true" world as seen by one who could ascend and view it from the purer ether that is above the air and surpasses it in the same degree that air surpasses seawater.

From there, looking down, we would see the "true earth" that would resemble "those balls which are made of twelve pieces of leather, variegated, a patchwork of colors, of which the colors that we know here -- those that our painters use -- are samples, as it were." Right away, the authors of Hamlet's Mill declare, we might suspect that we are talking about the heavens above, if we are familiar with the night sky and the division of the heavens into twelve segments along the ecliptic band (187), and they note that those who dogmatically insist that this cannot be correct might be advised to look closer.

Socrates then proceeds to describe the mythical rivers, first saying that they all flow together into the yawning void of Tartarus -- the biggest of all the chasms of the earth, he says, and the one that is bored right through the earth.

De Santillana and von Dechend then begin to muster evidence that Socrates (or Plato) is relating in this passage something more than a set of mythological rivers grounded only in fable (or "so much poetic nonsense," as they say on page 186). First they note that the river Okeanos described by Socrates and Hesiod as "deep-flowing," "flowing-back-on-itself," "untiring," "placidly flowing," and "without billows" may seem to describe an earthly ocean, but according to German mythologist E.H. von Berger (1836 - 1904) the adjectives used "suggest silence, regularity, depth, stillness, rotation -- what belongs really to the starry heaven" (190).

Then they note that the Orphic hymn 83 (probably penned in the first centuries AD) calls Oceanus the "ruler of the pole," a blatantly celestial description (191). Further, they point out that Numenius of Apamea (second century AD, a neopythagorean and an important exegete of Plato) declared that "the other world rivers and Tartaros itself are the 'region of planets'" (188).

Finally, they call upon the third manuscript of the anonymous Vatican Mythographer, who probably wrote between the ninth and eleventh centuries AD, explained that the Red River (Phlegethon or Pyriphlegethon) was meant "by certain writers" to be the exact counterpart of the circle of Mars in the skies." De Santillana and von Dechend exclaim, "So Numenius was not wrong after all. The rivers are planetary" (196).

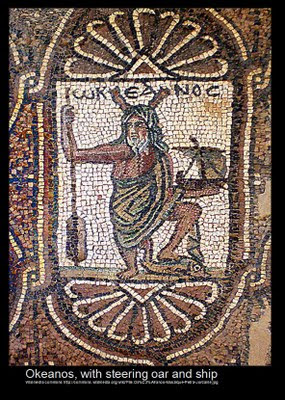

They also note that Oceanus was personified as a god or a Titan (pictured above, from a mosaic at Petra), and one who was curiously above the commands of Zeus, able to remain aloof even when Zeus commanded the presence of all the other gods. He maintains the characteristics of "remoteness and silence" in the words of de Santillana and von Dechend (191), just like the silent heavens themselves.

We can note a few other points from the ancient texts, such as the fact that Hesiod describes the river Oceanus as "winding about the earth and the sea's wide back" -- clearly indicating that Oceanus is different than the sea, as it winds around both the earth and the wide back of the earthly sea.

Further, we can note that Oceanus is described by Socrates as the river that flows "in a circle furthest from the centre" -- perhaps referring to the planetary course that is furthest from the sun. Note that the number of the rivers corresponds to the number of the visible planets known to the ancients -- Oceanus, Acheron, Pyriphlegethon, Styx and Cocytus corresponding perhaps from furthest to closest to Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, and Mercury. De Santillana and von Dechend present convincing evidence that the fiery river Pyriphlegethon (called simply Phlegethon by later authors) corresponds to the red planet Mars. Even if the rivers are called by different names later (sometimes Lethe is substituted for Oceanus, for instance), the number of the rivers flowing through the world of the dead remains the same as the number of visible planets.

This correspondence indicates that the realm of the dead where these rivers flow may well be the heavens, which is consistent with the beliefs of the ancient Egyptians inscribed in the Pyramid Texts (discussed here), in which the souls of the pharaohs are said to abide among the Imperishable Stars, and to other widespread ancient beliefs cited in Hamlet's Mill that the spirits of the dead travel through the Milky Way.

It also provides another piece of evidence that the myths of the ancients, which we may be tempted to dismiss as primitive notions left over from those who knew relatively little about the earth and the solar system, actually encode fairly sophisticated, even scientific knowledge. In fact, it provides another window on the possibility that very ancient myths were actually the carriers of encoded scientific knowledge, knowledge that in many ways surpassed even the achievements of the great Greek pioneers of scientific knowledge. This possibility raises the question of the identity of this ancient civilization that possessed and encoded ancient knowledge of this nature. (If these particular pieces of evidence are not enough to be convincing, consider them in conjunction with the data points discussed in this and this previous blog post).

In the Phaedo, Plato has recorded an example in which Socrates himself tells a tale which, like other ancient myths, seems fantastical and completely unbelievable on the face of it, but which on closer inspection contains metaphorical allusions to observations that would fall within the realm of what we today would classify as science, just as de Santillana and von Dechend allege the other myths about the gods do as well.

In Chapter XII of their work, Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend include a lengthy quotation from the Phaedo, focusing particularly on the description of "the earth" as seen from above, and the strange rivers which Socrates describes going around and through the earth in that dialogue. These rivers are Okeanos (Ocean), Acheron, Pyriphlegethon, Cocytus, and Styx.

In an impressive display of literary detective work, de Santillana and von Dechend reveal that the geography in the Socrates account corresponds not with earthly geography but with that of the heavens.

Socrates begins his description of "the true earth" with an analogy of the ocean, saying those who lived on the bottom of it would imagine that they inhabited the true earth, but if one could ever ascend to the surface and put his head out into the air, he would see a purer world above, not as prone to the corrosion of the sea-brine and the slime and mire of the watery world. In the same way, he says, we are living in a world less pure than the "true" world as seen by one who could ascend and view it from the purer ether that is above the air and surpasses it in the same degree that air surpasses seawater.

From there, looking down, we would see the "true earth" that would resemble "those balls which are made of twelve pieces of leather, variegated, a patchwork of colors, of which the colors that we know here -- those that our painters use -- are samples, as it were." Right away, the authors of Hamlet's Mill declare, we might suspect that we are talking about the heavens above, if we are familiar with the night sky and the division of the heavens into twelve segments along the ecliptic band (187), and they note that those who dogmatically insist that this cannot be correct might be advised to look closer.

Socrates then proceeds to describe the mythical rivers, first saying that they all flow together into the yawning void of Tartarus -- the biggest of all the chasms of the earth, he says, and the one that is bored right through the earth.

Now into this chasm all the rivers flow together, and then they all flow back out again; and their natures are determined by the sort of earth through which they flow. The reason why all these streams flow out of here and flow in is this, that this fluid has no bottom or resting place: it simply pulsates and surges upwards and downwards, and the air and the wind round about it does the same; they follow with it, whenever it rushes to the far side of the earth, and again whenever it rushes back to this side, and as the breath that men breathe is always exhaled and inhaled in succession, so the wind pulsates in unison with the fluid, creating terrible, unimaginable blasts as it enters and as it comes out. (quoted in Hamlet's Mill, 183).Socrates then goes on to briefly describe special rivers that he "would mention in particular." First is the largest, "which flows all round in a circle furthest from the centre" -- Okeanos or Oceanus, which Hesiod (probably sometime between 750 BC and 650 BC) said "winds about the earth and sea's wide back" with "nine silver-swirling streams" and then "falls into the main" (from Theogony, 790ff, quoted in Hamlet's Mill, 199). After that, he describes Acheron, Pyriphlegethon, Styx, and Cocytus.

De Santillana and von Dechend then begin to muster evidence that Socrates (or Plato) is relating in this passage something more than a set of mythological rivers grounded only in fable (or "so much poetic nonsense," as they say on page 186). First they note that the river Okeanos described by Socrates and Hesiod as "deep-flowing," "flowing-back-on-itself," "untiring," "placidly flowing," and "without billows" may seem to describe an earthly ocean, but according to German mythologist E.H. von Berger (1836 - 1904) the adjectives used "suggest silence, regularity, depth, stillness, rotation -- what belongs really to the starry heaven" (190).

Then they note that the Orphic hymn 83 (probably penned in the first centuries AD) calls Oceanus the "ruler of the pole," a blatantly celestial description (191). Further, they point out that Numenius of Apamea (second century AD, a neopythagorean and an important exegete of Plato) declared that "the other world rivers and Tartaros itself are the 'region of planets'" (188).

Finally, they call upon the third manuscript of the anonymous Vatican Mythographer, who probably wrote between the ninth and eleventh centuries AD, explained that the Red River (Phlegethon or Pyriphlegethon) was meant "by certain writers" to be the exact counterpart of the circle of Mars in the skies." De Santillana and von Dechend exclaim, "So Numenius was not wrong after all. The rivers are planetary" (196).

They also note that Oceanus was personified as a god or a Titan (pictured above, from a mosaic at Petra), and one who was curiously above the commands of Zeus, able to remain aloof even when Zeus commanded the presence of all the other gods. He maintains the characteristics of "remoteness and silence" in the words of de Santillana and von Dechend (191), just like the silent heavens themselves.

We can note a few other points from the ancient texts, such as the fact that Hesiod describes the river Oceanus as "winding about the earth and the sea's wide back" -- clearly indicating that Oceanus is different than the sea, as it winds around both the earth and the wide back of the earthly sea.

Further, we can note that Oceanus is described by Socrates as the river that flows "in a circle furthest from the centre" -- perhaps referring to the planetary course that is furthest from the sun. Note that the number of the rivers corresponds to the number of the visible planets known to the ancients -- Oceanus, Acheron, Pyriphlegethon, Styx and Cocytus corresponding perhaps from furthest to closest to Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, and Mercury. De Santillana and von Dechend present convincing evidence that the fiery river Pyriphlegethon (called simply Phlegethon by later authors) corresponds to the red planet Mars. Even if the rivers are called by different names later (sometimes Lethe is substituted for Oceanus, for instance), the number of the rivers flowing through the world of the dead remains the same as the number of visible planets.

This correspondence indicates that the realm of the dead where these rivers flow may well be the heavens, which is consistent with the beliefs of the ancient Egyptians inscribed in the Pyramid Texts (discussed here), in which the souls of the pharaohs are said to abide among the Imperishable Stars, and to other widespread ancient beliefs cited in Hamlet's Mill that the spirits of the dead travel through the Milky Way.

It also provides another piece of evidence that the myths of the ancients, which we may be tempted to dismiss as primitive notions left over from those who knew relatively little about the earth and the solar system, actually encode fairly sophisticated, even scientific knowledge. In fact, it provides another window on the possibility that very ancient myths were actually the carriers of encoded scientific knowledge, knowledge that in many ways surpassed even the achievements of the great Greek pioneers of scientific knowledge. This possibility raises the question of the identity of this ancient civilization that possessed and encoded ancient knowledge of this nature. (If these particular pieces of evidence are not enough to be convincing, consider them in conjunction with the data points discussed in this and this previous blog post).

In the Phaedo, Plato has recorded an example in which Socrates himself tells a tale which, like other ancient myths, seems fantastical and completely unbelievable on the face of it, but which on closer inspection contains metaphorical allusions to observations that would fall within the realm of what we today would classify as science, just as de Santillana and von Dechend allege the other myths about the gods do as well.