Conditions turned out to be just right for viewing the very young crescent moon in my neighborhood of the globe last evening.

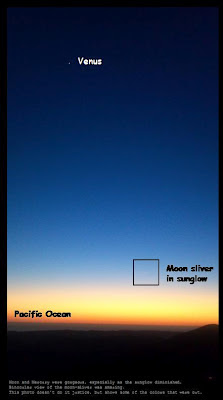

As the sun sank below the horizon, the brilliant planets Venus and Jupiter looked like jewels in the deepening blue high above, forming a line which pointed down towards the red glow where the sun had disappeared over the rim of the earth's horizon.

At first, the very fine sliver of the moon's arc was impossible to spot, but suddenly it was unmistakeable. The photograph above does not do it justice at all. Through binoculars it was breathtaking -- a thin silvery line, so thin that it was not even completely continuous. There is a gorgeous photograph on the web taken by photographer Stephano de Rosa which shows the same crescent over the Alps: this is very much what it looked like here, except that the color of the sky was different over the Pacific Ocean. Clicking on that photograph enlarges it for even better detail.

Just below and to the left, Mercury could be easily spotted through binoculars, a very small jewel sitting in a golden sea of the sun's glow (at first). As the rim of the earth continued to "rise up" (or the sun continued to retreat further below the horizon), this glow diminished and the moon and the planet Mercury became very distinct in the darker blue background. Mercury took on a very slight orange hue (almost yellow-orange).

This previous post outlined some of the mythological connections associated with the category of planetary events we are enjoying this month. The excellent video from Sky & Telescope's Tony Flanders shows where the crescent moon will be located tonight. As the sun continues to outpace the moon like a runner in a race that has passed another runner and continues to widen the gap, the moon trails the sun by a greater distance each day, and thus sits higher in the sky after sunset each evening. The crescent also thickens as the moon gets further from the sun (on its way to becoming full when the moon has gotten so far from the sun that it is now opposite to the sun from the observer on earth -- see previous discussions here and here).

Mr. Flanders also has an accompanying article which explains that last night's very thin crescent moon was about twenty-eight hours old when the sun was going down on the west coast of North America on the evening of February 22 (about twenty-four hours old for viewers along the east coast of the same continent). A link in that article takes you to another excellent Sky & Telescope discussion of very new crescent moons.

It explains that the window of sixteen to twenty-four hours after the precise moment of new moon is about the soonest one can observe the very thin crescent with the naked eye. The record for naked-eye observation of a new crescent is currently a moon that was only fifteen hours and thirty-two minutes old. A crescent only eleven hours and forty-two minutes old was observed with optical aid in 2002.

The second page of that article on observing very new crescents explains that astronomers have determined that the moon must be at least seven and a half degrees behind the sun for a crescent to begin to appear at all. Some of the work in this area was done by professor of astronomy Dr. Bradley Schaefer, who is mentioned in that article and also in this previous post discussing his important new analysis of the star catalogs of Ptolemy and Hipparchus (and his analysis of the Farnese Globe).

All five visible planets are now observable in the same evening. The planet Saturn rises later in the constellation Virgo, which follows Leo and retrograde Mars in the east.

As the sun sank below the horizon, the brilliant planets Venus and Jupiter looked like jewels in the deepening blue high above, forming a line which pointed down towards the red glow where the sun had disappeared over the rim of the earth's horizon.

At first, the very fine sliver of the moon's arc was impossible to spot, but suddenly it was unmistakeable. The photograph above does not do it justice at all. Through binoculars it was breathtaking -- a thin silvery line, so thin that it was not even completely continuous. There is a gorgeous photograph on the web taken by photographer Stephano de Rosa which shows the same crescent over the Alps: this is very much what it looked like here, except that the color of the sky was different over the Pacific Ocean. Clicking on that photograph enlarges it for even better detail.

Just below and to the left, Mercury could be easily spotted through binoculars, a very small jewel sitting in a golden sea of the sun's glow (at first). As the rim of the earth continued to "rise up" (or the sun continued to retreat further below the horizon), this glow diminished and the moon and the planet Mercury became very distinct in the darker blue background. Mercury took on a very slight orange hue (almost yellow-orange).

This previous post outlined some of the mythological connections associated with the category of planetary events we are enjoying this month. The excellent video from Sky & Telescope's Tony Flanders shows where the crescent moon will be located tonight. As the sun continues to outpace the moon like a runner in a race that has passed another runner and continues to widen the gap, the moon trails the sun by a greater distance each day, and thus sits higher in the sky after sunset each evening. The crescent also thickens as the moon gets further from the sun (on its way to becoming full when the moon has gotten so far from the sun that it is now opposite to the sun from the observer on earth -- see previous discussions here and here).

Mr. Flanders also has an accompanying article which explains that last night's very thin crescent moon was about twenty-eight hours old when the sun was going down on the west coast of North America on the evening of February 22 (about twenty-four hours old for viewers along the east coast of the same continent). A link in that article takes you to another excellent Sky & Telescope discussion of very new crescent moons.

It explains that the window of sixteen to twenty-four hours after the precise moment of new moon is about the soonest one can observe the very thin crescent with the naked eye. The record for naked-eye observation of a new crescent is currently a moon that was only fifteen hours and thirty-two minutes old. A crescent only eleven hours and forty-two minutes old was observed with optical aid in 2002.

The second page of that article on observing very new crescents explains that astronomers have determined that the moon must be at least seven and a half degrees behind the sun for a crescent to begin to appear at all. Some of the work in this area was done by professor of astronomy Dr. Bradley Schaefer, who is mentioned in that article and also in this previous post discussing his important new analysis of the star catalogs of Ptolemy and Hipparchus (and his analysis of the Farnese Globe).

All five visible planets are now observable in the same evening. The planet Saturn rises later in the constellation Virgo, which follows Leo and retrograde Mars in the east.