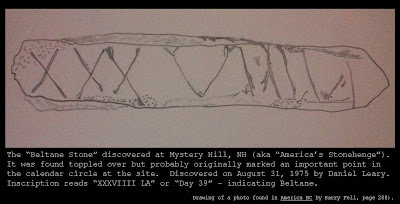

Above is a drawing of the "Beltane Stone" found at Mystery Hill, New Hampshire on August 31, 1975. The drawing is modeled on a photograph in Barry Fell's 1976 classic America BC: Ancient Settlers in the New World (page 200). That book details extensive examples of carvings and other artifacts found in the New World and evidencing usage of ancient languages and ancient writing systems known to historians of the Old World, including Phoenician, Egyptian, and Iberian (among others).

Mystery Hill, New Hampshire features a large calendar circle -- in this case a series of widely-dispersed stones which enable an observer from a central location to view the sunrise on important days of the year, which were marked by prominent upright stones (many triangular or fang-shaped) which lined up with the distant horizon. The sun can still be observed to rise and set behind these ancient markers to this day (some of the structures at the site may also indicate important lunar stations as well).

This previous post from October 30 of last year discussed the calendar circle in some detail, in light of the approach of an important cross-quarter day, Samhain, a station of the earth's orbit that is the opposite of the cross-quarter day now arriving, known anciently as Beltane. That post contained a diagram of the calendar circle at Mystery Hill indicating the positions of the stones and the direction to the sunrise or sunset on these important dates, which is reproduced below for convenience:

As discussed in several previous blog posts such as this one, the most well-known stations of the year are the solstices and equinoxes (two solstices and two equinoxes, for a total of four altogether), which divide the year into four sections (in other words, they "quarter" the year). Those important stations occur near our calendar dates of March 21 (the March equinox), June 21 (the June solstice), September 22 (the September equinox), and December 21 (the December solstice).

However, in between them there are four other dividing points, which are referred to as the "cross-quarter days," because they are in between the four "quartering" days, and indicate the point midway between each of the "quarters" created by the solstices and equinoxes. As can be seen from the above diagram of Mystery Hill and the date markers included at that site, these cross-quarter days were also of great importance in ancient cultures. In particular, Mystery Hill marks the cross-quarter day between the Fall or September Equinox and Winter Solstice (November 1, or Samhain) and it marks the cross-quarter day between the Spring or March Equinox and Summer Solstice (May 1, or Beltane), with rocks whose positions can be seen to this day (it also contains markers for the solstices and equinoxes themselves).

These important cross-quarter days very likely marked the beginning of winter and the beginning of summer, respectively. As this external article on the subject aptly points out, the solstices are traditionally called Midwinter and Midsummer, which makes sense if they were considered to be the middle of winter and summer, not the beginning (we often hear today that the June solstice marks the start of summer, but it is actually Midsummer). Thus, the cross-quarter days of Samhain and Beltane (halfway through the quarter of the year preceding Midwinter and Midsummer) would likely be the correct days to indicate the beginning of the winter and summer seasons.

Interestingly (and this has also been discussed in previous posts), the cross-quarter days may have once been reckoned on slightly different days, but migrated a few days to the beginning of their month for convenience. For example, Martin Brennan's excellent book the Stars and the Stones identifies the cross-quarter days as falling on May 6, August 8, November 8 and May 6 (again, see discussion here).

These dates create a more even number of days on either side of the cross-quarter days between the previous solstice or equinox and the next solstice or equinox. This website identifies the cross-quarter days for 2012 as falling on February 4, May 5, August 7, and November 7 (dates given are for those at Greenwich Mean Time -- due to the date-line convention, some parts of the globe will be in a different calendar day when the earth crosses the exact cross-quarter point, just as with the exact passage of the earth through the precise astronomical points of each of the solstices and equinoxes).

The number of days between one solstice/equinox and the next cross-quarter day, or between one cross-quarter day and the next solstice/equinox, generally works out to around 45 or 46 days (sometimes 47 and sometimes 44, and again this will depend on what calendar date is used for the count based on the date-line convention).

However, what is really fascinating is that the "Beltane Stone" depicted above contains an inscription in Roman numerals for the number "39" (in this case, it is rendered as "XXXVIIII"). Barry Fell believes this indicates "Day 39" -- identifying Beltane as falling 39 days after the Spring Equinox (the Spring Equinox being a traditional ancient start to the year, the day whose heliacal rising zodiac constellation named the entire Age, such as the Age of Taurus or the Age of Pisces or the future Age of Aquarius).

Fell writes that:

In 45 BC Julius Caesar instituted throughout the Roman Empire a new reformed calendar devised by the Greek astronomer Sosigenes. The date of the spring equinox was now set at March 25, and the new year was set to start on January 1. The Celts of New England, however, retained the old Celto-Greek New Year that began on the day of the spring equinox; in other respects they followed the revised Roman Calendar, presumably in order to facilitate business arrangements with overseas traders from Spain and Portugal. May 1, the great Mayday festival of the Celts, called Beltane, now fell on the thirty-ninth day of the year, a fact recorded in the Romano-Celtic inscription on the stone at Mystery Hill. [. . .] Hence the Beltane Stone dates from about the time of Christ, when the Mayday festival occurred on day 39 of the New England year. America BC, 200.

Fell's book details many other inscriptions from the New World -- many but by no means all of them in New England -- which feature dedications to the Celtic sun god Bel, from whom Beltane takes its name (appropriate, as the day marks the arrival of the "summer quarter" of the year, one eighth before Midsummer and the other eighth after Midsummer: the portion of the year most dominated by the sun).

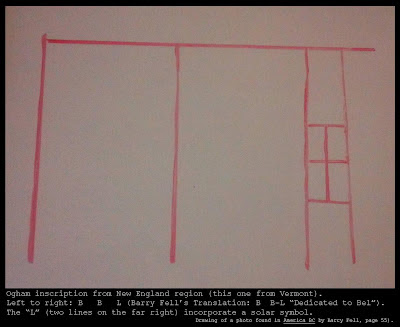

Most of the inscriptions mentioning Bel are in Ogham writing, discussed in this previous blog post and in greater detail in the Mathisen Corollary book itself. One of these, reproduced below (from page 55 of Fell's text), indicates the Ogham letters (from left-to-right in this case, although just as frequently these were written from right-to-left) "B" (the single line going down below the horizontal "stem-line"), followed by another "B" (another single carving line below the stem-line), followed by an "L" (the two lines closer to one another below the stem-line):

Barry Fell alleges that this inscription should be understood to read "B B-L," meaning "dedicated to Bel" (the Ogham inscriptions in the New World, like ancient Hebrew, did not usually include indications of the vowels, leaving that up to the reader based on context).

Note that the letter "L" is usually just two parallel lines below the stem: in this case, the ancient engraver decided to embellish his "L" with the "quartered" design that you can see between the carved vertical lines -- it looks something like a window-pane. Barry Fell alleges that this is a solar symbol, and indeed he produces photographs of a great many such symbols, often a quartered circle (like a Celtic Cross with four equal arms, or a circle with a "plus" symbol through it), which can clearly be seen to be associated with the sun.

Note that this quartered circle can very easily be understood to convey the sense of the four quarters of the year, divided by the solstices and equinoxes, and indeed you can see that the earth's path around the sun can be thought of as just such a quartered circle (see the diagram in this previous post, for instance). The inclusion of this solar symbol in the final letter of the inscription appears to be reinforcing evidence in support of Fell's translation of the inscription as a dedication to the solar deity Bel.

Fell also discusses another important inscription found on triangular stones at Mystery Hill inserted into the walls of the same chamber and containing writing on one in saying "Dedicated to Bel" in similar Ogham lines as those depicted above (without the "window pane" symbol) and "To Baal of the Canaanites, this dedication" in Iberian script and the Punic language on another (pages 90 - 91). About this find, Fell writes: "Bel is the Celtic sun god, long suspected (but until now never proven) to be the same god as the Phoenician Baal" (90 - 91).

Whether the existence of two inscriptions on two different tablets in the same ancient stone structure proves the direct identification of Bel with Baal is a matter for debate. However, the existence of these inscriptions at Mystery Hill and other sites (as well as the presence of a stone inscribed with Roman numerals) appears to be compelling evidence for ancient contact from across the oceans. Even if skeptics were to argue that the so-called "Beltane Stone" with its Roman numerals was the product of colonial settlers after Columbus, it would be difficult to argue that these later colonial-era settlers also produced the Ogham inscriptions.