On March 04, 2014, a fascinating paper appeared in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, entitled "The Vertebrates of the Late Jurassic Daohugou Biota of northeastern China," by Corwin Sullivan, Yuan Wang, David W. E. Hone, Yuanqing Wang, Xing Xu, and Fucheng Zhang.

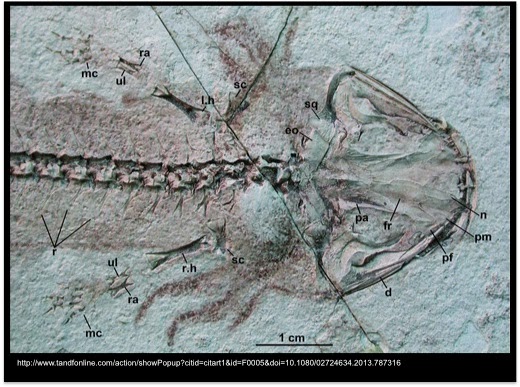

The paper discusses the amazing fossils from a region in Inner Monglolia, known as Daohugou, in which the fine-grained sand beds allowed for the preservation of fossilized soft-tissue features, including feather-like quills, the outlines of soft body-parts, and even the external gills of salamanders such as the Chunerpeton tianyiensis, shown above.

The paper discusses the distinctive features of the Daohugou beds and the fossilized fauna preserved there which both link them to other famous fossil beds in the northeastern region of China (including the Yixian, Dabeigou, and Jiufotang Formations), and distinguish Daohugou as having some unique aspects. The region has produced exquisitely-preserved fossils which the paper describes as including "plants, anostracans, conchostracans, arachnids, and insects, as well as vertebrates."

The paper discusses various dating estimates for the beds, generally in the neighborhood of 152 million years ago to 166 million years ago, based on radiometric dating techniques (although the paper notes some difficulties with those methods for this region) and on conventional models of the way the various geological layers were deposited (this blog has discussed numerous reasons why both of these methodologies may be completely incorrect, if in fact there was ever a cataclysmic world-wide flood event as described by Dr. Walt Brown's hydroplate theory: see this post and this post for some discussion of the problems with conventional radioactivity assumptions, and this post and this post for some discussion of the problems with conventional stratigraphy assumptions, among many others).

The presence of such delicately-preserved fossils, over such a wide geographic range, and in such depth (encompassing numerous different layers, with the Daohugou sometimes described as being part of the lower layers of the Yixian Formation), causes tremendous difficulties for conventional theories of fossilization and geographic stratification. Many of these problems were discussed in a previous post which examined the widespread findings of delicately-preserved jellyfish fossils in areas of the United States, entitled "Jellyfish fossils and the hydroplate theory."

One of the most obvious problems is the fact that delicate tissue, such as jellyfish bells and jellyfish tentacles, or the external gills on the fossil salamander shown above (and discussed in this section of the paper by Sullivan et al.), or the incredible gossamer insect-wings found in many fossils in the Yixian formation (see image here and at the bottom of this post) does not normally hang around long enough to be fossilized by the mechanisms envisioned under conventional, non-catastrophic theories of fossil formation. A dead insect lying on the forest floor, or the desert floor, will usually be eaten before it becomes a fossil. If it is not eaten by something larger, it will under normal conditions decompose and be devoured by microbes long before it becomes a fossil. Even simple things such as wind and rain will probably rip its wings off and destroy them long before they can be fossilized. The same goes for jellyfish washed up on a beach, or soft tissues such as the salamander gills shown above.

Even if extremely unusual conditions somehow preserved one insect with gossamer wings, or one salamander with external gills, or one jellyfish by some miraculous set of "just-right" circumstances, how can we possibly explain the abundance of jellyfish described in the earlier-linked post on jellyfish fossils, or the superabundance of insect-wings, salamanders with soft-tissue fossils, plants, and other incredibly well-preserved specimens from the now-famous regions of northeastern China? How do we explain not only the incredible number and variety of well-preserved specimens, but also the vast region in which they are found? Did "perfect conditions" just happen to occur -- not just along one isolated stream somewhere, but over a vast swath of Inner Mongolia?

And the conventional problem goes even deeper than that, because these exquisitely-preserved fossils in the Yinxian and Jiufotang and other formations are found not just along one layer of supposed geographic age, but among many layers -- implying that these "just right" conditions miraculously kept cropping up over and over throughout the course of tens of millions of years (but all in this one region of modern China)! This kind of explanation beggars belief. By the way, the jellyfish fossils of the regions of the modern-day US also appear in several different layers, thought by conventional scientists to represent many different ages of ancient history.

As usual, the king-sized problems that the conventional theory cannot adequately explain are handled extremely satisfactorily by Dr. Brown's hydroplate theory. On this page of Dr. Brown's book (which he graciously makes available to read in its entirety for free online, but which can also be purchased in hardcopy here), Dr. Brown compares the conventional explanation for the formation of the fossil evidence we find around the world with the hydroplate explanation, and allows readers to decide for themselves which explanation better fits the evidence we find. Dr. Brown's explanation involves the widespread liquefaction which would have taken place during a catastrophic flood event, and which would explain the thinly-pressed and delicately preserved fossils of the northeastern China region as well as the jellyfish fossils of North America. For a complete discussion of liquefaction, the interested reader is encouraged to read the entire chapter on liquefaction in Dr. Brown's book.

Many of the items from Dr. Brown's list (written long before this latest article appeared describing the fossilized specimens of the northeastern China region) fit very well with the description of the Daohugou and other localities in the recent article. Some of those include the presence of very fine basaltic sediments to great depths, the breadth of the region, and the sorting of fossils into various "biota" which distinguish one group from another (and which form the primary subject of this latest paper in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology).

The possibility that there has been a catastrophic event in this planet's past which is responsible for the fossils we find should not be so difficult to accept -- in fact, as this blog has discussed many times and as Dr. Brown's book discusses in far greater depth, the evidence overwhelmingly leads to that conclusion. However, such a possibility is so distasteful to the defenders of the conventional academic paradigms that it is almost never even considered, let alone accepted. This unfortunate bias leads to the acceptance of explanations which should be infinitely more difficult for someone to believe, explanations which posit the perfect conditions that could preserve salamander gills, jellyfish bells, or insect wings not just one time but many times, over wide regions stretching for miles in all directions, and in multiple layers which were formed many millions of years apart!

Perhaps someday some of those scientists who currently talk themselves into believing such fantasies will stop and take a look at the much more scientific explanations offered in the hydroplate theory.