image: Stellarium (stellarium.org).

Observers of the night sky have for some time now been watching with great anticipation the steady approach of the planet Jupiter to dazzling Venus in the western sky during the hours after sunset.

The two are now extremely close, just over one degree apart on June 28. As described in the always-helpful "This Week's Sky at a Glance," from Sky & Telescope, the two will be a mere 0.6 degrees apart on June 29, and reach their closest point on June 30 when they will close to 0.3 degrees before Jupiter passes on and continues on his way. (Note that these dates are based on the the date effective for an observer located in most of the western hemisphere and North America in particular, but if you are located in another part of the globe you should be able to easily find a site on the web that will tell you what the calendar date will be in your area when these passages take place).

In the image above, you can see Jupiter approaching Venus directly above the letter "W" that signifies the cardinal direction west. Jupiter is located higher in the sky and towards the "left" for an observer facing west in the northern hemisphere -- Jupiter has been approaching Venus from further east on the ecliptic path that both the planets generally follow: that is to say, from the direction of the star Regulus which is also marked on the diagram above and which is located in the zodiac constellation of Leo the Lion, the importance of which will be discussed a bit later.

It is not hard to imagine why the approach of one significant celestial body to another in this manner was frequently allegorized as a seduction or a sexual liaison in the world's mythologies. During the buildup to a previous "close approach" of Jupiter to Venus, back in 2012, I discussed the fact that Zeus (Jupiter) was described in ancient mythology as pursuing Aphrodite (Venus) but being rejected by her and not actually having direct sexual relations with her, and that this detail from the myths is no doubt derived from the fact that Jupiter always passes close to Venus but the two never actually conjoin in the sky.

One might wonder why Venus is very often depicted as a female goddess, while Mars, Jupiter and Saturn are depicted as male gods. I believe it has to do with the fact that as an interior planet -- with an orbit that is within the orbit of the earth, relative to the sun (Venus orbiting on a path closer to the sun than does the earth) -- an observer on earth must always look in the general direction of the sun in order to see Venus (if you are having trouble visualizing this, there are some outstanding diagrams on the excellent website of Nick Anthony Fiorenza, here, and some further discussion of the celestial mechanics of our observation of Venus in a previous blog post here).

What this means is that Venus will never be seen to be very far from either the western horizon that the sun has just disappeared beneath (when the sun sets and Venus is on the part of her orbit when she is seen in the west) or from the eastern horizon whence the sun is preparing to burst forth in the morning (when the sun is getting ready to rise and Venus is on the part of her orbit when she is seen in the east). In other words, Venus will always be "tethered" to the sun and thus will never be seen ranging across the middle of the sky at midnight: Venus will always be seen above either the western horizon or the eastern horizon, in fairly close company to the sun (currently, Venus is seen above the western horizon, after the sun sets).

On the other hand, the "outer planets" whose orbits are outside of the earth's orbit around the sun (they orbit at a distance from the sun greater than the distance of earth's orbit) can be seen to range across the entire night sky. They always follow the same general "track" of the ecliptic path ( the path that the sun also follows, as well as the moon, although the moon like the planets can deviate by a small number of degrees either above or below the ecliptic line that the sun follows), but along this track they can be seen across the entire width of the sky -- unlike the interior planets who are "tethered" to the sun.

This means that Jupiter, Mars, and Saturn can be seen crossing the middle of the sky at midnight, when an observer on earth is turned completely away from the sun. A planet in the middle of the sky at midnight can only be located outside the orbit of the earth (because an observer on earth looking into the center of the sky at midnight is looking out into the heavens in the opposite direction from the sun, which is on the other side of the earth at that time). So Venus can never be seen out in that direction (neither can Mercury, whose characteristics will be addressed in a moment).

Because of these mechanics, Jupiter, Mars and Saturn can all approach Venus from the center of the sky, as Jupiter is doing now, and when they do so, they resemble a man pursuing a woman, or advancing their cause with a woman to seek either marriage or an amorous liaison with her.

Of course we all know that it is also possible for a woman to pursue a man, and such pursuits are certainly portrayed in the ancient myths -- but when Jupiter is striding across the sky in a long, purposeful pursuit of the beautiful shining Venus, as he has been doing for some time now and getting closer every night, the ancients allegorized this behavior in mythology as the confident but amorous leader of the gods chasing after the goddess of beauty in order to have an affair with her.

As for Mercury, his orbit is even closer to the sun than that of Venus, and so he can only be seen under the same conditions that we see Venus, but "even more so." Tethered even more tightly to the sun, Mercury can only be observed above the eastern horizon just before the sun comes up, or above the western horizon just after the sun goes down, and the planet has an even more limited range above the horizon (and away from the sun) than does Venus. Thus, Mercury is usually seen being approached by Venus, rather than the other way around -- and so he is the one who is described in myth as being pursued by the love goddess.

Once we understand that it was very common for these close conjunctions of celestial bodies to be described in mythology as sexual affairs, we can perhaps unravel what seems to be a very important theme found in more than one myth across different cultures: the situation in which a woman is described as having five husbands.

In the Mahabharata, for instance, one of the two epic Sanskrit poems of ancient India (and which by itself is equal to about 7.2 times the combined length of the Iliad and the Odyssey), the five principle heroes of the story -- the Pandavas or "sons of Pandu" -- are actually the children of the two wives of Pandu but by five different gods or divinities.

Pandu's two wives are Kunti (also known as Pritha) and Madri. Because of an incident in which the glorious Pandu while out hunting thoughtlessly shot a stag while it was mating, which turned out to be no ordinary stag but rather a powerful rishi in the form of a stag, who before expiring told Pandu that he would meet his death the next time he approached one of his wives out of desire, Pandu took vows of strict austerity and abstinence. Therefore, in order to obtain children, Pandu instructed his wives to use a powerful mantra which could instantly summon the celestial powers, which they did.

Kunti first summoned the god of justice in his spiritual form, and from their union was born the eldest of the Pandavas, Yudhishthira. After that, she used her mantra to cause to appear the god of wind in his spiritual form, and from their union was born the mighty Bhima, who is also known as Vrikodara. Then, a third time, she used the mantra, and this time summoned Sakra, the king of the gods, and from their union was born the great hero Arjuna.

Then, Kunti told Madri the secret of the mantra, who used it to summon the divine Twins, known as the Ashvins, and from their union Madri herself had twins, whose names were Nakula and Sahadeva. The description of the births of Yudhishthira, Bhima, Arjuna, and the twins Nakula and Sahadeva can be found in Book I and sections 123 and 124.

Together, these five heroes were known as the Pandavas. The Mahabharata relates many stories of their adventures during their upbringing, and how they were versed in the Vedas and in all the martial arts as they grew up. Their tremendous prowess caused their cousins, the descendants of Pandu's brother Dhritarastra, to become very jealous of them, leading to intense rivalry and eventually to the battle of Kurukshetra, which forms some of the central action of the Mahabharata, the celestial and spiritual aspects of which have been discussed in the two preceding blog posts and accompanying videos: here and here (with videos here and here).

Interestingly enough, when the mighty archer Arjuna won the hand of Draupadi, the Princess of Panchala and the most beautiful woman in the world, in a heroic test of his prowess designed by her father to test her many suitors, she becomes the common wife of all five of the brothers!

This situation arises because as they returned to the hut where Kunti was waiting for them, and called out to Kunti to see what they had won, she said (before they came into her view): "Enjoy ye all what hath been obtained," which leads them to decide to all share Draupadi (she appears to be amenable to this situation) but which is so directly contrary to custom and to the directives found in Vedic scripture that it leads to several discussions with leading human figures and with gods about whether or not such an arrangement can be proper, before it is finally decided that it is not usual but it can be condoned in certain situations (see Book I and sections 193 and following -- note that the Roman numerals used in the online version of the Mahabharata linked here are incorrect in this instance: the second "L" should be a "C," according to my analysis of the chapters and my understanding of the system).

However, as with so many other events described in the ancient myths, scriptures, and sacred stories, this is a situation which I believe has a celestial foundation and in no way reflects something that we should interpret literally -- any more than we should interpret literally the Old Testament stories about the rash vow of the reluctant general Jephthah, or about the two she-bears summoned by the prophet Elisha to rend the youths who taunted him.

To understand why this situation of Draupadi marrying all five Pandava brothers is almost certainly a celestial myth and not mean to be understood literally, first consider the fact that it seems to mirror very closely the five different divine fathers of the Pandavas themselves (although with two different women, Kunti and Madri, rather than with a single woman). What is it about five different "husbands" in mythology?

While we ponder that question, readers who are familiar with the scriptures of the Bible may be asking themselves whether there could be any relationship between these "five-husband" situations in the Mahabharata and the famous episode described in the New Testament book of John, chapter 4. There, Jesus is described as going through a city of Samaria, and coming to Jacob's well, and being wearied with his journey sitting down to rest at the well, where he encounters a woman of Samaria, and asking her for drink.

During the course of the conversation, he tells her to call her husband, and she tells him she has no husband, whereupon Jesus replies:

Thou hast well said, I have no husband:

For thou hast had five husbands; and he whom thou now hast is not thy husband: in that saidst thou truly [John 4:17 - 18].

This passage has been the subject of much interpretation and debate amongst those who try to understand it as if it were describing a literal and historical event, but I believe that here again we are dealing with a celestial allegory. It is certainly remarkable to find a situation with five "husbands" in the New Testament scriptures which parallels so closely the "five-husband pattern" that we have just observed operating not once but twice in the stories contained in the Mahabharata of ancient India (which scholars believe to have been in existence in many of its central details by about 400 BC, and to contain stories and episodes whose origin goes back many centuries earlier than that).

I believe that we can begin to unravel the celestial metaphor at work in these "five-husband" myths, based on the understanding of the pattern of sexual allegory observed in the approach of Jupiter to Venus with which we began this discussion, above, and which can also be seen operating in other ancient myths such as the Greek myth of the dalliance between Aphrodite and Ares described in the Odyssey, in which the rightful husband of Aphrodite, Hephaestus, springs a trap for his unfaithful wife -- and which the author's of Hamlet's Mill (basing their analysis on the work of previous researchers from the eighteenth century and even from ancient times) argue is an allegorization of a conjunction between the planets Venus and Jupiter in the vicinity of the Pleiades (which represent the shimmering net with which Hephaestus traps the adulterous couple).

Now, it is certainly possible to interpret the identity of the Samaritan woman at the well in John 4 as being associated with the zodiac constellation of Virgo -- and indeed, I believe the story contains clues to make an identification with Virgo in this particular story a correct connection, as we will see in a moment.

However, I believe that the part of the story of the woman at the well in which we learn that she has "five husbands" comes from somewhere other than the sign or constellation of Virgo.

Seeing that the woman in many ancient myths is often related somehow to the sign and the constellation of Virgo, we might first try to use that knowledge to find the origin of the multiple husbands. We might ask ourselves, how would an identification with Virgo explain this persistent pattern of "five husbands" which we have observed in both the Mahabharata and the John 4 episodes?

What could there be in the heavens that add up to the number five and that somehow pursue Virgo in a way that could be allegorized in this way? Well, we know that there are five visible planets which an observer on earth can easily see with the naked eye: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. It could be that the "five husbands" represent the five visible planets, passing through the constellation Virgo at various times, and giving rise to these myths about one woman having five husbands -- but I do not believe that this is the correct interpretation, for a couple of reasons.

First, as we have already seen, out of the five visible planets, Venus and Mercury are "interior planets" and thus they stay closely "tethered" to the sun. Because of this fact, and because of the planet's brilliance and beauty in the sky, Venus is usually depicted as a female goddess, who is "pursued" by the outer planets. This would seem to disqualify Venus from being one of the "husbands" if we are trying to count the five visible planets as the five husbands.

More importantly, the interpretation of the "five-husband pattern" as being based upon the constellation Virgo being visited by the five different visible planets does not work very well as an interpretation of the myth of the birth of the five Pandavas by the two wives of Pandu, Kunti and Madri, because Madri is specifically described as calling upon the twin Ashvins using the mantra, and by union with these divine Twins she herself bears the twin Pandavas, Nakula and Sahadeva. The celestial Twins are associated not with two of the visible planets (none of which can really be described as a "twin" to any of the others), but rather with the constellation of Gemini, the Twins. Because the Twins of Gemini do not "make their way" across the sky to the constellation Virgo, it is likely that the solution to the "five-husband pattern" is something else.

I believe that in the case of the two wives of Pandu, Kunti and Madri, we are dealing with the two interior planets, Venus and Mercury -- with Kunti (the primary consort of Pandu) corresponding to Venus and Madri corresponding to Mercury. Additional evidence to support this interpretation is found in an episode related in Book I, section 125: after the birth of the five Pandavas, Pandu forgets his vows when he is overwhelmed by Madri's beauty as they are alone in a place of great natural beauty during the spring when all the trees are blossoming, and as he approaches her in his passion, he perishes because of the curse described above (from the time he shot the rishi, who had taken the shape of a stag).

Madri, stricken with grief, decides to immolate herself upon Pandu's funeral pyre. Again, I believe that this event is not to be taken literally, but rather that it describes quite well the behavior of the planet Mercury, which is very close to the sun and always seen near the sun (not far above the western horizon after sunset, or not far above the eastern horizon before the dawn). Mercury can only be seen by an observer on earth when its orbit takes it farthest out from the sun: during much of its orbit, Mercury is either in front of the sun or behind the sun, or too close to the sun on one side or the other to be seen by an observer from earth. To an observer on earth, Mercury is often "swallowed up" by the sun as its orbit takes it too close to the blazing orb to be seen by us.

I believe that in these myths, Pandu is the sun itself (and specifically the sun in the upper half of the zodiac wheel, as is Achilles in the Iliad), and his two wives Kunti and Madri are Venus and Mercury, respectively: the two planets closest to the sun, and always appearing in his close vicinity.

Who, then, can be the five husbands who become the divine fathers of the five Pandauvas? They cannot be the three remaining visible planets, which obviously do not add up to five, and who would not account for the fact that Madri has union with the divine Twins (and, as we have just observed with the planet Jupiter, its orbit does not bring it close enough to Venus to actually "consummate" the union: the two pass one another on either side of the ecliptic line).

The answer, I believe, lies in the detail of the Twins who are the divine progenitors of Nakula and Sahadeva: the five husbands are five bright stars along the ecliptic path, found in different zodiac constellations, whose location in the sky will cause them to pass close enough to Venus (or Mercury) to be envisioned as having a "sexual union" with them.

When one of the planets actually covers another celestial object (from the perspective of an observer on earth), this is known as "occultation" (similar to a solar eclipse, which uses the term "occultation" to describe the covering of the sun by the intervening moon). If Venus were to completely cover a bright first-magnitude star, for example, this would be referred to as "occulting" that star -- and it would create a situation that would allegorically resemble sexual union (even more than what will take place in the next few days between Jupiter and Venus).

It just so happens that there are three first-magnitude stars which are close enough to the path of the ecliptic to be occulted by the planets -- including by Venus. They are the stars

- Regulus (in Leo the Lion, which is along the line created by Jupiter and Venus right now, and a little above and to the left of the two approaching planets, for observers in the northern hemisphere above the tropics),

- Antares (in the heart of the Scorpion),

- and Spica (the brightest star in Virgo).

I believe that these are the three celestial divinities who, in their spiritual forms, fathered the first three Pandavas by Kunti (producing Yudhishthira, Bhima, and Arjuna).

The other two bright stars in the zodiac close enough to the celestial equator to be contenders are in fact the two bright stars who form the heads of the Twins of Gemini: Pollux and Castor. However, they are not close enough to be occulted, although in the distant past it is likely that they were (due to the changing of the earth's obliquity over the millennia, and the motion of precession). In spite of the fact that they do not currently lie in a location that can allow them to be directly occulted, because the Mahabharata specifically states that Madri summoned the celestial Twins, it is almost certain that these two stars constitute the other two "husbands" and round out the five.

In the case of Draupadi, we no longer are dealing with "two wives of Pandu" but only "one wife of all five Pandauvas," and since she is described as being the most beautiful and the most dazzling woman on earth, she is almost certainly the brilliant planet Venus (Mercury is not part of this particular "five-husband metaphor"). But, she still takes as her husbands the three first-magnitude zodiac stars Regulus (probably Yudhishthira), Antares (probably Bhima) and Spica (probably Arjuna), plus the stars of the Twins: Pollux and Castor (Nakula and Sahadeva).

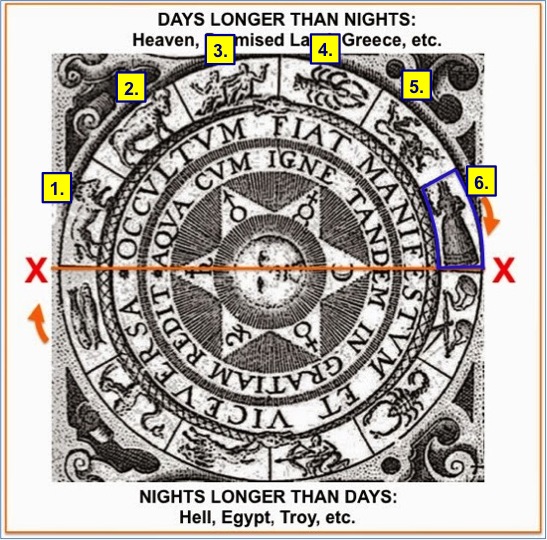

Here is a diagram of the night sky facing to the south for an observer in the northern hemisphere, showing Venus and Jupiter, as well as Regulus just to their "left" (or east of them), Pollux and Castor (to their "right" or west, not far from the glow of the sun which can be seen setting in the west), and further east the first-magnitude stars Spica and Antares:

Note that Spica and Antares are actually located "below" or south of the celestial equator, which is the "latitude line" of zero degrees that can be seen arcing between the letters "E" and "W" in the simulated celestial "globe" above. The "latitude line" (properly termed the "parallels of declination") above that celestial equator zero-line is the ten-degree parallel: stars located along it are said to have a "declination" of ten degrees north, or "plus-ten" degrees. The parallel of declination below (to the south) of the zero-line of the celestial equator is the minus-ten parallel. Stars along it have a declination of ten degrees south, or "minus-ten" degrees. Because the line of the ecliptic "yawns" above and below the celestial equator as we go throughout the year by as much as 23.4 degrees (due to the tilt of the earth's axial rotation, also called "the obliquity of the ecliptic"), the planets and the sun and moon (which basically follow the track of the ecliptic) can "occult" the stars north and south of the celestial equator.

Thus, it is my present belief that the "five-husband" pattern found in the Mahabharata and in the New Testament book of John with the Samaritan woman at the well can be understood as mythologizing the allegorical "unions" of the brilliant feminine planet Venus with the five stars Regulus, Antares, Spica, and the Twins of Gemini.

Trying to make sense of the Samaritan woman at the well when interpreted literally rather than celestially causes some difficulties, as the perceptive analysis here (from someone who believes the story was intended to describe a literal-historical event) points out. That analysis first discusses the textual clue of Jesus arriving at the well "at about the sixth hour" (John 4:6). He argues that this means the time corresponding to what we would call six in the evening, not twelve noon as other literalist interpreters have tried to argue as part of their thesis that the woman must have been an outcast (due to the community's rejection of her having had five husbands).

How could she have obtained five husbands, if she was supposedly rejected by the community, this interpreter asks? And why would the community have listened to her after her encounter with Jesus? And, most importantly, if the whole community rejected her because of her five husbands, then the fact must have been common knowledge, and the fact that Jesus told it to her would not have been all that surprising, and would certainly not have led to her realization that he was the Messiah!

These kinds of literal analyses, however, are probably missing the point of the story as celestial allegory. While I believe that the "five-husband" pattern found in this New Testament story is a feature of ancient myth (as evidenced by its existence in the Mahabharata, from many hundred years BC), I believe that the "sixth hour" reference in this passage specifically refers to the constellation Virgo.

As already discussed at some length in the video about the goddess Durga, and the reason that Arjuna is urged by Lord Krishna to utter his hymn to Durga upon "the eve of battle," the zodiac sign of Virgo is located at the very "gateway" to the lower half of the zodiac wheel: metaphorically the half of the wheel associated with incarnation, where we undergo the endless interaction and struggle between the realms of matter and spirit, and the half of the wheel allegorized as the underworld, as well as with the ocean (and with water, one of the two "lower elements," along with earth).

Hence, the "woman at the well" -- at the edge of the lower element of water -- would correspond nicely with the sign of Virgo: and the fact that Virgo is the SIXTH sign of the zodiac during the Age of Aries (as counted from Aries, the first sign after the "upward crossing" at the spring equinox, the beginning of the sacred year in many ancient cultures) makes the connection between the woman at the well and the zodiac sign of Virgo almost a certainty.

We are also told specifically in the New Testament passage that the Samaritan woman "left her water pot, and went her way into the city" in John 4:28. This is another detail which helps connect her with Virgo -- because right besides Virgo in the heavens is the sinuous form of Hydra, the Serpent, who carries on his back the constellations of Corvus the Crow (a bright little constellation very close to Virgo, and always staring at her brightest star Spica, in fact) and Crater the Cup -- which is also near to Virgo and which can certainly be said to resemble a "water pot," thus accounting for this detail in the text.

Now, the reader may be wondering at this point, "But what does all this mean?"

I believe, in fact, that the meaning of these Star Myths is quite profound, and that the message they are intended to convey is extremely helpful to us in our daily lives -- even extremely practical. Some aspects of that message are discussed in the previous posts and videos linked already (in the discussions of the Bhagavad Gita and of the Hymn to Durga, both found in the Mahabharata). See also the discussion and metaphor found in the post just prior to those, entitled "Self, the senses, and the mind."

Those previous discussions, of aspects of the Mahabharata, explained that these Star Myths may well be intended to convey the knowledge that we have access -- immediately and at all times -- to what we might call "the infinite" or "the absolute" or "the unbounded" (and which cannot in fact be defined, because the very act of "defining" something means to draw a boundary around it), and that this access to the infinite is found within us.

I believe that we can see this message being conveyed again in the mythical birth of each of the Pandavas, in which Kunti and Madri are depicted as uttering a powerful mantra which has the ability to immediately summon a divine celestial power. If reciting a mantra can summon divinity, and if that divinity actually appears immediately, then these are two clues to point us towards the possible conclusion that the divinity is actually within us, all along.

But we can also, I believe, see the same message being conveyed in the story of the woman at the well. There, Jesus says to the woman that if she would ask, he would have given her "living water." This water, he says, is such that whosoever drinketh of it shall never thirst: "but the water that I shall give him shall be in him a well of water springing up into everlasting life" (John 4:14).

Note that this water is described as being "everlasting" -- it is, in fact, infinite. It has no ending, and thus no "boundary" in at least one direction.

Secondly, note that the promised water is found "within" the one who is given it. The contact with the infinite, in other words, is somehow inside of us.

And, just like the story of Kunti and Madri, all we actually have to do in order to obtain this intimate union with the infinite, is ask.

When they ask, the divine powers appear immediately.

In the teaching of John chapter four, the infinite well of living water is obtained in a similar fashion: by simply asking -- because we are already in contact with the infinite.

Ultimately, these stories are not just there to entertain us: they have a very powerful message, and one that can actually transform our lives.

This gives us plenty to meditate upon, as we watch the beautiful near-conjunction of Venus and Jupiter taking place in the celestial realms this week.

image: Wikimedia commons (link).