Astute longtime readers of this blog and of my books and writings which discuss connections between the stars and the myths may have noticed that in the previous post's interview with Oscar Inclan of Lords of Consciousness, I discussed the celestial foundations for the myths of ancient Greece involving the marvelous metal being named Talos -- and that I have not previously discussed Talos in any of my published works or various interviews.

Talos is a figure described by ancient sources as being a kind of enormous living statue formed of bronze and capable of autonomous action and thought, created by the god of fire and metalworking, Hephaistos (or Hephaestus). In most of the stories, he was stationed upon the island of Crete and served the people there -- and guarded the island by making a circuit around it three times each day. In the event of any unfriendly invaders, the metal giant would break off great boulders from the cliffs and hurl them at their ships.

In fact, more than one ancient author describe the encounter with Talos and the Argonauts, and the giant's prevention of the Argonauts from landing at Crete when they were desperately tired and in need of water.

In the various ancient accounts describing Talos, he is described as having a single vein or vessel to pump the ichor upon which his life and autonomous motion depended, which ran from his neck down to the sinew of his ankle -- and in all the stories describing his demise, this vessel is opened at his heel, allowing his life-giving ichor to flow out and bring about the end of the marvelous bronze giant.

In some accounts, the vein is ripped open by a sharp rock of a cliff, and in others the screw or nail which sealed the ichor inside the mechanical being was removed -- in most versions by Medea or Medeia, who had a complex relationship with Jason and accompanied the Argo on most of its voyages. She was a powerful figure who in some versions of the story enchanted Talos in order to exploit his vulnerable heel, and in other versions promised him transformation into a flesh-and-blood man if he would drink a certain potion, which clouded his judgment and slowed his reactions so that the nail could be removed. In other accounts, the vulnerable heel of the giant was pierced by a well-placed arrow, in a similarity to the stories of the demise of the great warrior Achilles.

The clip above shows some footage of the iconic depiction of the giant Talos in the movie Jason and the Argonauts from 1963, featuring the groundbreaking stop-motion animation of special effects genius Ray Harryhausen. The movie takes some liberty with various aspects of the myth of Jason and the Argonauts, and the demise of Talos in the film does not involve any special assistance from Medea (instead, the giant basically stands still while the critical stopper on the back of his heel is unscrewed), but it nevertheless memorably brings to life the majesty and power (and even pathos) of the legendary bronze giant in a way that is difficult to surpass.

The ancient story of the mysterious metal automaton is one which certainly has the power to capture the imagination, and one which has sparked a variety of attempts to explain it through a process of what I would categorize as varieties of "literalization" -- trying to tie the origins of the myth to actual literal mechanical devices, such as ancient robots (perhaps manufactured by aliens) or to ancient techniques of sculpting (as argued by Robert Graves in The Greek Myths, published in 1955 -- see page 317 of Volume I).

However, as I discussed in the previously-mentioned interview from Contact in the Desert, this myth almost certainly has a celestial origin -- as do virtually all of the world's other ancient myths, scriptures and sacred stories. I believe that the identity of the bronze giant who meets his end when the stopper holding his animating fluid is removed can be definitively linked to the mighty constellation Orion -- and the celestial "river" that can be seen originating from the vicinity of the foot of that heavenly giant.

That celestial river is the constellation Eridanus, a long line of stars originating near the bright star Rigel in the forward (or westernmost) foot of the constellation Orion. The name of this heavenly stream can clearly be seen to have linguistic parallels with the name of the Jordan River on earth. The name Eridanus may also be connected in some way to the name of the ancient city of Eridu in Mesopotamia, near the Euphrates River, as suggested by the authors of Hamlet's Mill (see for example pages 257 - 258).

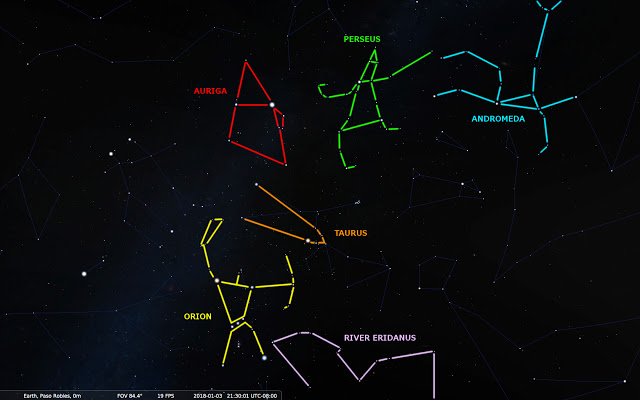

Below is an image of the night sky showing the location of the River Eridanus relative to the towering figure of the constellation Orion (he looks much larger in real life than the flat screen image can portray -- and this should give some indication of the sheer length of the River Eridanus in the sky):

Those objecting to the argument that the River Eridanus could be seen as flowing out of the forward foot of Orion might be expected to point out that the constellation Eridanus does not actually "connect" with the figure of Orion proper. However, as I have explained in some of the volumes of the series Star Myths of the World and how to interpret them, the ancient myths can be shown to envision "additional lines" connecting nearby constellations at times, such as the "added line" envisioned between the lower arm of the constellation Hercules and the Northern Crown (Corona Borealis), when Hercules is envisioned as grasping an arching infant in numerous myths and sacred stories (such as the story of the Judgment of Solomon in the Hebrew Scriptures).

In the above diagram of Orion and Eridanus, we can see that an "additional line" can easily be envisioned between the bright star Rigel which marks the toe or foot of Orion and the second star in the stream of the heavenly river (or even the first star in the stream, for that matter, although the second star in Eridanus is closest to Rigel) . This is the first clue that the story of Talos and his vulnerability are linked to the constellation Orion and the river of fluid that appears to stream out of his foot or ankle region.

Additional confirmation for this identification would be desirable, however -- and the myths themselves appear to provide us with further supporting clues which help to give confidence in the assertion that Talos in this story corresponds to Orion. In most versions of the story, Talos is a creation of the god Hephaestus. There are some versions in which Talos is a creation of the great inventor, Daedalus -- and I would argue that these versions probably give us a clue that Daedalus could be associated with the same constellation which often plays the role of Hephaestus. We will set aside discussion of Daedalus for another day, and concentrate for now on the identity of Hephaestus. Hephaestus, the divine smith and god of fire, is described in ancient myth as being lame in both feet, due to having been hurled from Olympus by either Zeus or Hera (depending on the version of the myth). Due to his injuries from the fall to earth (which took an entire day, in some accounts), he is often depicted as riding upon a donkey -- but in some accounts he also is attended by golden automatons which he has fashioned and which support him from either side. In the Iliad, these are described as being female servants fashioned of gold, whom the poet describes as being:

all cast in gold but a match for living, breathing girls. Intelligence fills their hearts, voice and strength their frames, from the deathless gods they've learned their works of hand. Book 18, lines 489 - 490. Translation by Robert Fagles.

In the diagram below, we see the constellations which are located directly above the constellation we're considering as a candidate for the figure of Talos (that is, Orion). Note that the figure of Perseus is not far from Orion in the night sky, above Orion (from the perspective of an observer in the northern hemisphere):

Note that one of the distinctive characteristics of the outline of Perseus is the fact that his feet are "twisted" -- this aspect of the constellation is very clearly visible when you locate Perseus in the night sky. I am convinced that this aspect of the constellation gives rise to the fact that Hephaestus also has twisted feet from his injuries sustained when he was hurled from the heights of Olympus.

For this reason, Hephaestus is sometimes described in ancient Greek myth -- and depicted in ancient Greek artwork -- as riding upon a donkey. Note that immediately below Perseus in the night sky we see the outline of the constellation Taurus the Bull, the most distinctive portions of which I have outlined in orange in the above star-chart: the V-shaped Hyades and beyond them the two long "horns" of the Bull. These long horns can be shown to also have been envisioned as the long ears of an ass or donkey in ancient myth (in fact, when Orion plays the role of Samson in the book of Judges in the Hebrew Scriptures, he reaches out his hand to grasp the "jawbone of an ass," represented by the V-shaped stars of the Hyades, as described in Hamlet's Mill on page 166).

Additional confirmation of the fact that Perseus with his twisted foot or feet was sometimes anciently envisioned as riding on a donkey represented by Taurus is seen in the story of Balaam (also from the book of Judges in the Hebrew Scriptures), which I outline at length in this previous post. In that story, Balaam has his foot "crushed" against a wall when the donkey sees an angel blocking the way.

As can be seen from the diagram, Taurus is directly above Orion in the sky -- and so if Hephaestus is sometimes envisioned as riding on a donkey, he could also be seen as being carried upon the shoulders of Talos, if Talos is represented by Orion. The fact that the metallic servants who support the god Hephaestus in the description in Book 18 of the Iliad are described as being female, however, may mean that the ancient myth is here envisioning the constellation Andromeda as one of the golden robots who supports the god in his workshop. In any case, the proximity of Orion to Perseus, and the fact that Hephaestus is almost certainly associated with that constellation Perseus (as well as being associated with the act of making metallic servants to assist him, which are located nearby in the night sky) is additional evidence that Talos is associated with Orion (in addition to the river of fluid flowing out of the foot of that constellation).

In fact, on pages 177 - 178 of Hamlet's Mill, the authors actually suggest that Talos is identified with Orion, although they do not clearly sketch out their reasons for making this assertion (this is somewhat characteristic of Hamlet's Mill in many instances).

Additional confirmation that the figure of Perseus probably plays the role of Hephaestus in many myths is found in the fact that the god is sometimes described or depicted as wearing headgear similar to the headgear suggested by the outline of the constellation. See for instance the depiction of Hephaestus and Thetis in this ancient red-figure vase, in which the divine smith is wearing a cap very similar in shape to the cap of Perseus in the night sky. That image of Hephaestus comes from the website theoi.com, which is a good resource for mythical information. If you visit the theoi page dealing with the god Hephaistos, you will see that image and another image from ancient Greek pottery depicting the god riding on a donkey.

Thus, I believe we can confidently conclude that the giant Talos is associated with the mighty figure of Orion in the night sky. It is very interesting to note the strong parallels between the donkey-riding figures of Balaam from the Old Testament of the Bible and Hephaestus from ancient Greece, and the evidence that both figures are almost certainly related to the same constellations in the night sky. This is further evidence that all the world's ancient myths, scriptures and sacred stories are in fact closely related, and based upon the same common worldwide system of celestial metaphor.

That ancient system, I am convinced, was designed to impart profound wisdom which is vital to our lives, even to our lives today in this modern age. I am also convinced that many of the most severe injustices and imbalances in our world today are directly related to centuries of disconnection from the fountain of this ancient wisdom, particularly in the cultures that would become known as "the west."

There are many lessons we could take away from the story of Talos. The idea of a mechanical automaton that circles the island of Crete, ostensibly to help the people, but who sometimes makes mistakes regarding its choice of targets (attacking the voyagers on the Argo, for example, when all they wanted to do was go ashore to replenish their supplies of water), should be thought-provoking in this era of weaponized drones, especially to those who are aware of the incredible advances taking place in the field of "artificial intelligence," "autonomous vehicles," and "machine learning.

If you have not thought about the enormous potential dangers of the horrifying rise of weaponized drones over the past sixteen years, led by the government of the united states -- or even if you have thought about it and already think you know how terrible this development is -- you should stop whatever else you are doing and watch the documentary National Bird.

Then you should ask yourself what life will be like when weaponized drones are routinely patrolling every inch of the surface of our planet, and not just faraway lands that are easy for many in "the west" to avoid thinking about.

Then you should ask yourself what it will be like when those weaponized drones are controlled, not by human beings (as horrible a prospect as that in itself would be) but rather by computer algorithms and artificial intelligence, algorithms which will guide their decisions regarding whether or not to unleash their firepower, like Talos breaking off gigantic boulders from the cliffs of Crete to hurl at the Argonauts.

Then you should ask yourself how to stop such an eventuality before it comes to pass, through committed nonviolent citizen action, education, and protest.

Otherwise, future generations may find themselves trying to figure out where the screw is in the heel of Talos.